The self-portrait has an enduring appeal for giving us an insight into how the artist perceives him or herself, or how he wishes to be perceived by viewers. Here I will consider a number of (largely modern) self-portraits, in a bid to explore the possible uses and aims of the form. Those included are by no means comprehensive, with some notable absences (I don’t mention a single van Gogh), but have been chosen as I feel they can be interestingly linked, and provide an insight into the varying and developing role of the self-portrait painting.

How an artist depicts himself relates closely to the common perception of what an artist is, and what constitutes a great artist. Older portraits, pre-19th century, tend to focus on the artist as a craftsman, and his technical skill. For instance, Rembrandt’s self-portrait famously depict him in front of the perfect circle, the ultimate expression of an artist’s skill. Later artists depicts themselves out of the studio setting, as the definition of ‘great artist’ came to be understood as one with a unique view and understanding of the world around him. So these later portraits often have blank, non-specific backgrounds, and focus on the artist’s expression, not on pointing out his skill.

This general move away from depicting oneself in the studio setting can be traced alongside the desire by some artists to picture themselves as a continuation of the great tradition of painting, maintaining high standards rather than pursuing any new styles. Ingres, an artist consumed by the desire to relate himself back to the great classical tradition, depicts himself in the typical setting, draped with a sort of cloak, stood before the easel.

The German Expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner first depicts himself in the studio, with brush and model, a typical subject. He is depicting himself as a master of his craft, his authority over the viewer expressed through his wild, staring eyes, and his dominance over the picture space. But here he seems to use this traditional setting to emphasise the radical differences in his style. He uses this touch of the familiar to shock the viewer, it is a provocative piece. But we maintain the emphasis on him as a painter, there is little sense of introversion, we are not being presented with an insight into his mind, rather a manifesto of his movement. This piece is particularly interesting when compared to his later self-portrait ‘Self-portrait of the Artist as a Soldier’, painted after he was invalided out of the First World War. Now we see all the introversion, his loss of confidence in himself and his artistic vision. His hand was not really blown off, but it is the hand which would have held his brush, expressing his loss of artistic voice (although we see that his style is little changed, and no less technically skilled). This is almost painting as therapy; through it Kirchner is able to express his inner turmoil and trauma.

This second self-portrait is more typical of the 20th and 21st century approach, when the artist’s world view has become at least as important as his technical skill, and the self-portrait becomes a means of self-exploration. Munch followed his usual unsettling lines of thought in his self-portrait, his head white, floating in the blackness above the skeletal arm and hand. We cannot help by search for meaning within the man himself. He was a deeply troubled man, terrified of feminine control, his family mostly killed by TB, one of his two remaining sisters resident in an asylum. This is not hard to guess from the portrait, but it remains mysterious and enigmatic, it’s meaning unspecified. This sense of mystery is often apparent in modern portraits, which sometimes act almost to imbue the artist with a sense of gravitas and mystery, rather than simply being used as a display of wealth and skill as they had been previously.

Exploration of identity is another common theme in modern self-portraits. Picasso’s self-portrait with ovoid eyes strengthens his Spanish identity at a time when he was one of only a few Spaniards in Paris (particularly among the art scene). Frida Kahlo has perhaps explored this use of the self-portrait more than any other artist. The vast majority of her painting are self-portraits, in which she explores her identity as a woman, threatened by her inability to bear children, as an artist, and as an individual. Although not technically a member of the Surrealist movement (in the European or American form), her work is often called Surrealist due to her exploration of dreams and dreamlike scenarios.

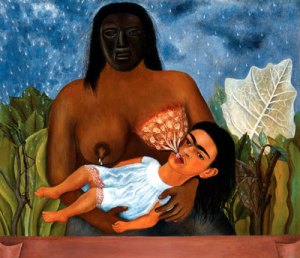

‘The Two Fridas’ explicitly explores her feelings regarding her Mexican identity, after the split between her and her husband Diego Rivera. The daughter of a Mexican mother and a European father, the piece expresses her feelings of being torn between the two cultural identities. ‘My Nurse and I’ of 1937, also explores her relationship with her mother, and her Mexican roots, the nurse’s face substituted for a proto-American mask, suggesting the way in which cultural heritage is passed down through the generations, and the strength that it has given her.

Kahlo’s frequent self-portraits highlight another more pragmatic side which has made them popular with artists throughout history: they are cheap. The model is free, and available whenever the artists wishes. Kahlo began painting whilst bed-bound, recovering from the bus accident which nearly killed her and robbed her of her ability to mother children. She was thus the obvious subject for her works. Taking a short aside further into history, this ready availability seems to have made self-portraits popular amongst female artists. Largely un-professional, women artists were often constrained by social requirements. There could be no question of impropriety if the woman were not aiming to paint for material gain, and even better, did not hire models, of either gender. For instance, Sofonisba Anguissola, active in the 16th and early 17thcenturies,

was highly acclaimed during her time, but stuck to portraits, with self-portraits, and portraits of family and close friends making up the majority of her output. From an aristocratic background, painting such close associates could not raise any suspicions, and she was in fact encouraged by her family to pursue her enthusiasm, albeit at an almost amateur scale. She did however go on to paint portraits of the Spanish court, including Phillip II and his family. Modern female artists have not been so restricted, but still return to the self-portrait. Tracy Emin’s 1998 ‘My Bed’ reads as an auto-biographical piece; a portrait of herself and her feelings seen through the objects with which she surrounded herself.

So we see that the self-portrait form is continuing to develop, even to include the abstract forms and installation art of the modern world. I have considered only a few ideas, any comments or thoughts would be greatly appreciated, it is an area which really fascinates me, and I think will continue to fascinate audiences due to the insight it gives us into the mind and feelings of the artist depicted.

I think this is brilliant Nel. xxx

LikeLike

[…] being used that differently to how their art historical precedents were? As I’ve explored before on this blog, there are numerous reasons why artists might choose themselves as subjects. But […]

LikeLike