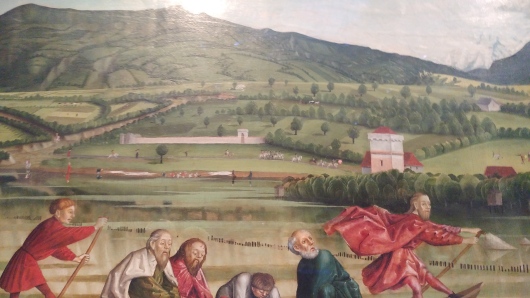

This painting, in Geneva’s Museum of History and Art, is picked out in their guide booklets as one of the 10 masterpieces of the Museum’s collection. It is truly a charming example of the Northern Renaissance interest in using the familiar to bring Biblical stories to life, as well as that attention to naturalistic detail which is striking in so many of the works of Northern European artists in this period. Originally part of an altarpiece, the scene is painted in oils on panel. The scene depicted is most likely the second of two miracles commonly referred to as the miraculous draught. One evening after Jesus’ resurrection, seven of the Disciples go fishing, and catch nothing. Next morning they try again, and once again have no luck. Jesus, who they do not recognise, calls to them from the shore: ‘Friends, haven’t you any fish?’ Hearing that they haven’t, he instructs them to cast their next on the right side of the boat, and they will find some. They do so, and the net is so full of fish that they can hardly lift it. By this miraculous change of fortune John recognises Jesus, and Peter jumps into the water to meet him. The exact number of fish caught is listed as 153, but Witz wisely does not seem to have troubled himself to paint every single one, the gist of the story being much the same whatever the number. He has however carefully chosen to illustrate other identifying aspects of the story: the seven disciples, the net being cast on the right side of the boat, and the dramatic moment when Peter jumps in to meet Jesus, arms outstretched and face bearing an expression of awe.

During this period it was becoming typical for artists to relocate Biblical narratives to local setting. Here Lac Leman stands in for the Sea of Galilee, the mountains in the background recognisable to his viewers. There is some debate as to why this became so popular, but it is easy to see that this gives the images a relatability and an immediacy which would be appealing to viewers. Rather than being distant, geographically and historically, the figures are given contemporary clothing, and situated such that the viewer would almost feel it was a scene they had stumbled upon in their own neighbourhood. In the fifteenth century there was a new focus on the individual’s personal role in securing their religious well-being. Individual prayer become more important, and people were taught to truly engage with religious stories and ideas, rather than being passive receptors of preaching. The rise of the Book of Hours is testament to this, as are the growth of spiritual groups of lay people. This was reflected in the art that was popular in this period, such as the new trend for depicting the Madonna and Child in an average, Netherlandish home. However, as we see here, it could also be seen in landscape settings. The Mountains, the Swiss Flag (already in use, but not of course to represent exactly the same area), the familiar architecture, and the scenes of mercantile activity on the right, all help to position this as a contemporary scene, aiding the viewer’s understanding of and engagement with the Biblical story.

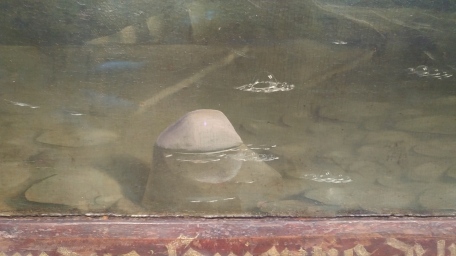

It is not only in what he has chosen to depict that Witz shows us an interest in realism. His attention to accurately depicting smaller details suggest a desire to create a naturalistic image. You get a real sense that he is painting based on observation of the real world. For instance, there is a clear attempt to depict the odd way in which light distorts our view of Peter’s submerged legs. There is also an impressive understanding of reflection, seen in the buildings on the right, but particularly in the reflections of the Disciples in the water alongside the boat.  We see ripples where the oar has left the water, and the small clusters of bubbles suggest where the water flows quickly amongst the rocks of the shore line. One can’t deny that some aspects are more crude (the grass on the shore is quite simplified), and he is not against an artistic flourish, the rippling folds of the first Disciple are more a demonstration of his skill than serving any other function, or fitting how the wind seems to be behaving in the rest of the scene But overall the effect is one of placing us in the scene, and confronting us with the essence of the story, not distracted by unfamiliar details which would pull us out of it. He seems keen to avoid any elements that would break this effect: the halos for instance, are the slightest of touches, more manipulations of light (again with an almost scientific eye for effects) than anything tangible. It is, all-in-all a highly impressive work, pleasing in its realism, but also capturing and embodying the religious preoccupations of its time.

We see ripples where the oar has left the water, and the small clusters of bubbles suggest where the water flows quickly amongst the rocks of the shore line. One can’t deny that some aspects are more crude (the grass on the shore is quite simplified), and he is not against an artistic flourish, the rippling folds of the first Disciple are more a demonstration of his skill than serving any other function, or fitting how the wind seems to be behaving in the rest of the scene But overall the effect is one of placing us in the scene, and confronting us with the essence of the story, not distracted by unfamiliar details which would pull us out of it. He seems keen to avoid any elements that would break this effect: the halos for instance, are the slightest of touches, more manipulations of light (again with an almost scientific eye for effects) than anything tangible. It is, all-in-all a highly impressive work, pleasing in its realism, but also capturing and embodying the religious preoccupations of its time.